KNOWPIA

BIENVENIDOS A KNOWPIA

Summary

Los afroestadounidenses son una minoría demográfica en Estados Unidos, descendientes de esclavos traídos de África, liberados por ley durante la Guerra de Secesión pero víctimas de segregación racial hasta mediados del siglo XX. Los primeros logros de los afroestadounidenses en varios campos hace referencia a un cambio cultural extendido, recopilado en la frase: "romper la barrera del color"[1][2]

Un ejemplo citado frecuentemente en este tema es Jackie Robinson, primer beisbolista afroestadounidense de la era moderna en convertirse en jugador en la Major League Baseball en 1947, terminando así con 60 años de las llamadas Ligas Negras, equivalente a la liga de béisbol pero para personas de color.[3]

Siglo XVIII

editar1738

editar- Primera comunidad afroamericana libre: Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose (más tarde llamada Fort Mose) en la Florida española.

1760

editar- Primer autor afroamericano conocido: Jupiter Hammon (poema "An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries", publicado como broadside)[4]

1768

editar- Primer afroamericano elegido como funcionario: Wentworth Cheswell, alguacil local en Newmarket, New Hampshire.[5]

1773

editar- Primera mujer afroamericana en publicar un libro: Phillis Wheatley (Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral)[6]

- Primera iglesia afroamericana separada: Silver Bluff Baptist Church, en el Condado de Aiken, Carolina del Sur[7][8][Note 1]

1778

editar- Primer regimiento militar afroestadounidense: 1st Rhode Island Regiment.[9]

1783

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en practicar la medicina formalmente: James Derham, aún sin titulación de médico.[10]

1792

editar- Primer afroestadounidense del Movimiento por la vuelta a África: 3.000 esclavos lealistas negros a la Corona inglesa, que habían escapado a las líneas británicas durante la Guerra de Independencia de los Estados Unidos por la promesa de la libertad se asientan en Nueva Escocia. Más adelante, 1.200 de ellos emigrarán a la nueva colonia británica de Freetown, desde donde se desarrollará Sierra Leona, en África.

1793

editar- Primera Iglesia Episcopal Metodista Africana: Richard Allen funda la "Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church", en Filadelfia, Pensilvania

Siglo XIX

editar1816

editar- Primera denominación religiosa evangélica afroestadounidense: la Iglesia Episcopal Metodista Africana (AME), con base en Filadelfia, Pennsilvania y varios estados del este.

1821

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en crear una patente: Thomas L. Jennings, para un proceso de limpieza en seco.[11]

1822

editar- Primer afroestadounidense capitán de un barco con toda su tripulación negra: Absalom Boston.[12]

1823

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en graduarse en una universidad: Alexander Twilight, en el Middlebury College.[13] (Véase también la sección de 1836)

1827

editar- Primer afroestadounidense propietario de un periódico: el Freedom's Journal, fundado en New York City por Peter Williams, Jr. entre otras personas de color.

1836

editar- Primer afroestadounidense elegido para un puesto público que sirve en una legislatura a escala estatal: Alexander Twilight, por Vermont.[13] (Véase también la sección de 1823)

1837

editar- Primer afroestadounidense médico colegiado: Dr. James McCune Smith de Nueva York, educado en la University of Glasgow, en Escocia, quien retorna para trabajar en la urbe neoyorquina.[14] (Ver también: 1783, 1847)

1845

editar- Primer afroestadounidense abogado: Macon Allen del colegio de abogados de Boston.[15]

1847

editar- Primer afroestadounidense médico graduado en una universidad estadounidense: Dr. David J. Peck.[16] en el Rush Medical College.

- Primer afroestadounidense presidente de alguna nación: Joseph Jenkins Roberts, presidente de Liberia[17]

1849

editar- Primer afroestadounidense profesor de una universidad predominantemente blanca: Charles L. Reason, del New York Central College.[18]

1853

editar- Primera novela publicada por una persona afroestadounidense: Clotel o la hija del presidente, de William Wells Brown, quien vivía en Londres en el momento de la publicación.[Note 2][19][20]

1854

editar- Primer instituto de educación superior que enseña a afroestadounidenses: el Ashmun Institute en Pensilvania, renombrada Lincoln University en 1866.

1858

editar- Primera obra teatral publicada por un afroestadounidense: The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom de William Wells Brown.[21]

- Primera mujer profesora de universidad: Sarah Jane Woodson Early, Wilberforce College[22]

1861

editar- Primera unidad militar con oficiales afroestadounidenses: 1st Louisiana Native Guard del Ejército Confederado.

- Primer afroestadounidense contratado como empleado en el Servicio Postal de los Estados Unidos: William Cooper Nell.[23]

1862

editar- Primera mujer afroestadounidense en obtener un Bachelor of Arts: Mary Jane Patterson, en el Oberlin College.[24]

- Primera unidad combatiente afroestadounidense reconocida en la U.S. Army: 1st South Carolina Volunteers.

1863

editar- Primera universidad propiedad y dirigida por afroestadounidenses: la Wilberforce University en Ohio.[25][Note 3] (Véase también la sección de 1854)

- Primer afroestadounidense en presidir una universidad: Daniel Payne (Wilberforce University).[26]

1864

editar- Primera mujer afroestadounidense en graduarse en Medicina: Rebecca Lee Crumpler, (New England Female Medical College).

1865

editar- Primer afroestadounidense field officer en la Armada de los Estados Unidos: Martin Delany.[27]

- Primer afroestadounidense admitido como abogado ante la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos: John Stewart Rock.[28]

- Primer afroestadounidense comisionado como capitán del Ejército de los Estados Unidos: Orindatus Simon Bolivar Wall, conocido como OSB Wall.[29]

1866

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en obtener un Doctorado: Patrick Francis Healy de la Universidad Católica de Lovaina, Bélgica.[30] (Véase también las secciones de 1851 y 1874)

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense alistada en la U.S. Army: Cathay Williams.[31]

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense profesora: Sarah Jane Woodson Early; la Ohio's Wilberforce University la contrató para enseñar latín e inglés.

1868

editar- Primer afroestadounidense elegido vicegobernador: Oscar Dunn (Luisiana).[32]

- Primer alcalde afroestadounidense: Pierre Caliste Landry, en Donaldsonville (Luisiana).[33]

- Primer afroestadounidense elegido para la Cámara de Representantes: John Willis Menard.[34] Su oponente recurrió su victoria no pudiendo ocupar su escaño. (ver: 1870)

1869

editar- Primer diplomático afroestadounidense: Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett, embajador en Haití (1869-1877).[35]

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense directora de una escuela: Fanny Jackson Coppin (Institute for Colored Youth).[36]

1870

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en votar en una elección bajo el 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, que garantiza el voto con independencia de la raza: Thomas Mundy Peterson.[37]

- Primer afroestadounidense en graduarse en el Harvard College: Richard Theodore Greener.[38]

- Primer afroestadounidense en ser elegido al Senado de los Estados Unidos y primero en servir en el Congreso: Hiram Rhodes Revels (R-MS).[39][Note 4]

- Primer afroestadounidense en servir (no sólo en ser elegido para ello) en la Cámara de Representantes: Joseph Rainey (R-SC).[40][Note 5]

1872

editar- Primer afroestadounidense midshipman admitido en la Academia Naval: John H. Conyers (nominado por Robert B. Elliott de Carolina del Sur).[41]

- Primer afroestadounidense gobernador (no elegido): P. B. S. Pinchback de Luisiana.[42]

- Primer afroestadounidense nominado a vicepresidente de EE. UU.: Frederick Douglass por el Equal Rights Party.[43][Note 6]

1874

editar- Primer afroestadounidense presidente de una universidad: Patrick Francis Healy, S.J. de la Universidad de Georgetown.[30] (Véase también las secciones de 1851, 1863 y 1866)

- Primer afroestadounidense en presidir la Cámara de Representantes como portavoz: Joseph Rainey.[44]

1876

editar- Primer afroestadounidense doctorado en una universidad de EE. UU.: Edward Alexander Bouchet (Yale College Ph.D., physics; también primero en graduarse en Yale, 1874)[45] (Véase también la sección de 1866)

1877

editar- Primer graduado afroestadounidense en la Academia Militar de los Estados Unidos: Henry Ossian Flipper.[46]

1878

editar- Primer afroestadounidense oficial de policía, en Boston, Massachusetts: Sargento Horatio Julius Homer.[47]

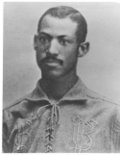

- Primer beisbolista profesional afroestadounidense: John W. "Bud" Fowler.[48]

1879

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en graduarse de una escuela de enfermería: Mary Eliza Mahoney, Boston, Massachusetts.[49]

1880

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en dirigir un barco de la Armada: Capitán Michael Healy.[50]

1881

editar- Primer afroestadounidense cuya firma aparece en moneda estadounidense: Blanche K. Bruce, registradora del Tesoro.[51]

1883

editar- Primera mujer afroestadounidense conocida en graduarse en uno de los Seven Sisters colleges: Hortense Parker (Mount Holyoke College)[52][Note 7]

1884

editar- Primer afroestadounidense beisbolista profesional en la liga mayor: Moses Fleetwood Walker.[53] (Véase también la sección de Jackie Robinson, 1947)

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense en crear una patente: Judy W. Reed, en la mejora de una amasadora, Washington D. C.[54][Note 8]

1891

editar- Primer oficial de policía de la ciudad de Nueva York: Wiley Overton, contratado por el departamento de policía de Brooklyn.[55] (Véase también la sección de Samuel J. Battle, 1911)

1892

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en cantar en el Carnegie Hall: la cantante de ópera Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones.[56]

- Primer nombre afroestadounidense en un equipo de fútbol americano: William H. Lewis, de la Harvard University.[57]

1895

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en obtener un doctorado en la Universidad de Harvard: William Edward Burghardt Du Bois.[58]

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense que trabaja en el servicio de Correo postal: Mary Fields.[59]

1898

editar- Primer afroestadounidense elegido pagador del ejército: Richard R. Wright

1899

editar- Primer afroestadounidense que consigue un campeonato del mundo en cualquier deporte: Marshall Major Taylor, en la milla ciclista.[60]

Siglo XX

editar1901

editar- Primer afroestadounidense invitado a una cena en la Casa Blanca: Booker T. Washington.[61]

1902

editar- Primer afroestadounidense jugador de baloncesto profesional: Harry Lew (New England Professional Basketball League).[62] (Véase también la sección de 1950)

- Primer campeón afroestadounidense de boxeo: Joe Gans de peso ligero.

1903

editar- Primer musical de Broadway escrito por y con estrellas afroestadounidenses: In Dahomey.

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense presidenta de un banco: Maggie L. Walker, del St. Luke Penny Savings Bank (desde 1930 Consolidated Bank & Trust Company), Richmond, Virginia.[63]

1904

editar- Primera fraternidad establecida por afroestadounidenses: Sigma Pi Phi.

- Primer afroestadounidense en participar en unos juegos olímpicos y también en ganar una medalla:: George Poage (dos medallas de bronce).[64]

1906

editar- Primera fraternidad inter-colleges por afroestadounidenses: Alpha Phi Alpha (ΑΦΑ), de la Cornell University.

1907

editar- Primer afroestadounidense de la iglesia ortodoxa griega: Robert Josias Morgan.[65]

1908

editar- Primer boxeador afroestadounidense de peso-pesado: Jack Johnson.[66]

- Primer afroestadounidense en ganar una medalla olímpica de oro: John Taylor.[67] (Ver también: DeHart Hubbard, 1924)

1910

editar- Primera mujer afroestadounidense millonaria: Madam C. J. Walker.[68]

1920

editar- Primeros afroestadounidenses en jugar como profesionales en la National Football League: Fritz Pollard (Akron Pros) y Bobby Marshall (Rock Island Independents).[69]

1921

editar- Primera mujer afroestadounidense en ser piloto de aviación y obtener una licencia internacional de piloto: Bessie Coleman.[70]

- Primer entrenador afroestadounidense de la NFL: Fritz Pollard, junto con Akron Pros.[69]

- Primera mujer afroestadounidense en conseguir el Doctorado en el país: Sadie Tanner Mossell, con un doctorado en Economía por la Universidad de Pensilvania.[71]

1924

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en ganar una medalla olímpica de oro en deporte individual: DeHart Hubbard, en la modalidad de salto de longitud, durante las olimpiadas de verano de 1924.[72] (Véase también la sección de John Taylor, 1908)

1925

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en ser funcionario de exteriores (en:Foreign Service Officer): Clifton R. Wharton, Sr.[73]

1927

editar- Primer afroestadounidense en trabajar de oficinista en el Departamento de Bomberos de la Ciudad de Nueva York: Wesley Augustus Williams.[74]

- Primera actriz afroestadounidense en aparecer como estrella en una película internacional: Josephine Baker en La Sirène des tropiques.[75]

1928

editar- Primer afroestadounidense elegido para la Cámara de Representantes tras el período de Reconstrucción: Oscar Stanton De Priest, por el partido Republicano en Illinois.[76]

1929

editar- Primer afroestadounidense comentarista de deportes: Sherman "Jocko" Maxwell (WNJR, Newark (Nueva Jersey).[77]

1932

editar- Primera jueza de raza negra de Estados Unidos: Jane Matilda Bolin. fue también la primera mujer en licenciarse en Derecho en la Universidad de Yale.

1939

editar- Primera actriz afroestadounidense en ganar un premio Óscar: Hattie McDaniel por Lo que el viento se llevó.

Siglo XXI

editar2020

editar- Primer jefe del Estado Mayor de la Fuerza Aérea y de cualquier rama militar: Charles Q. Brown, Jr.[78]

2022

editar- Primer general de cuatro estrellas del Cuerpo de Marines: Michael Langley.[79]

Véase también

editar- Portal:Afroestadounidenses en la Wikipedia en inglés.

Notas

editar- ↑ This claim is contested by the First Baptist Church, Petersburg, Virginia (1774) and the First Colored Baptist Church, renamed First African Baptist Church, Savannah, Georgia (1777).

- ↑ Because it was published in the U.K., the book is not the first African-American novel published in the United States. This credit goes to one of two disputed books: Harriet Wilson's Our Nig (1859), brought to light by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in 1982; or Julia C. Collins' The Curse of Caste; or The Slave Bride (1865), brought to light by William L. Andrews, an English literature professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Mitch Kachun, a history professor at Western Michigan University, in 2006. Andrews and Kachun document Our Nig as a novelized autobiography, and argue that The Curse of Caste is the first fully fictional novel by an African American to be published in the U.S.

- ↑ Founded earlier; not fully owned and operated by African Americans until 1863

- ↑ Revels, the Mississippi State Senate's Adams County representative, was elected by the U.S. Senate in January 1870 to fill an unexpired term.

- ↑ Rainey, a South Carolina state senator, was elected to fill the seat vacated by B. Franklin Whittemore. Rainey took his seat on December 12, 1870. John Willis Menard was actually the first African-American elected to the House (1868) but he was denied his seat.

- ↑ Douglass did not seek the nomination or campaign after being nominated.

- ↑ Parker graduated from Mount Holyoke when it was still a seminary.

- ↑ This was previously thought to be Sarah E. Goode (for the cabinet bed, Chicago, Illinois).[54]

Referencias

editar- ↑ Juguo, Zhang (2001). W. E. B. Du Bois: The Quest for the Abolition of the Color Line. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93087-1

- ↑ Herbst, Philip H (1997). The Color of Words: An Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ethnic Bias in the United States. Intercultural Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-877864-97-1

- ↑ Sailes, Gary Alan (1998). "Jackie Robinson: Breaking the Color Barrier in Team Sports". African Americans in Sport: Contemporary Themes, Transaction Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7658-0440-2

- ↑ O'Neale, Sondra (2002). «Hammon, Jupiter». En William L Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, Trudier Harris (eds.), ed. The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195138832.

- ↑ He was of mixed race, one-quarter African and three-quarters European, and listed in the US Census as white.

- ↑ Shields, John C. (27 de julio de 2010). Phillis Wheatley and the Romantics. University of Tennessee Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-57233-712-1. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Raboteau, Albert J. (2004). Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-19-517413-7. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Brooks, Walter H. (1 de abril de 1922). «The Priority of the Silver Bluff Church and its Promoters». The Journal of Negro History 7 (2): 172-196. ISSN 0022-2992. doi:10.2307/2713524. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Haverington, Christine (16 de julio de 2012). Middletown. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-9248-0. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Jacobs, Claude F. (2007). «James Derham (b. 1762)». En Junius P. Rodriguez (ed.), ed. Slavery in the United States: a social, political, and historical encyclopedia 2. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851095445.

- ↑ Alexander, Leslie M. «Jennings, Thomas L.». Encyclopedia of African American History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 455-457. ISBN 1851097694.

- ↑ «Whaling Museum and Peter Foulger Museum». Museum of African American History. Archivado desde el original el 7 de junio de 2014. Consultado el 5 de junio de 2014.

- ↑ a b Melish, Joanne P. (1998). Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and "race" in New England, 1780-1860. Cornell University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8014-3413-6. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Byrd, W. Michael; Clayton, Linda A. (21 de agosto de 2000). An American Health Dilemma: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race: Beginnings to 1900. Taylor & Francis. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-203-90410-7. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ «Long Road to Justice: The African American Experienced in the Massachusetts Courts». The Massachusetts Historical Society. 1845. Archivado desde el original el 28 de agosto de 2014. Consultado el 15 de febrero de 2008.

- ↑ Ward, Thomas J. (2003). Black physicians in the Jim Crow South. University of Arkansas Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-61075-072-1. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Anzovin, Steven; Podell, Janet (2001). Famous first facts about American politics. H.W. Wilson. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8242-0971-1.

- ↑ Jackson, Sandra; Johnson, Richard Greggory (2011). The black professoriat: negotiating a habitable space in the academy. Peter Lang. pp. 2-4. ISBN 978-1-4331-1027-6. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Dinitia Smith (28 de octubre de 2006). «A Slave Story Is Rediscovered, and a Dispute Begins». The New York Times. pp. B7. Consultado el 15 de febrero de 2008.

- ↑ Sven Birkerts (29 de octubre de 2006). «Emancipation Days». The New York Times. Consultado el 15 de febrero de 2008.

- ↑ Zack, Naomi (1995). American mixed race: the culture of microdiversity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8476-8013-9. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Philip Sheldon Foner; Robert James Branham, eds. (1998). Lift every voice: African American oratory, 1787-1900. Studies in rhetoric and communication. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 384-385. ISBN 978-0-8173-0906-0. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Rubio, Philip F. (2010). There's Always Work at the Post Office: African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality. Univ. of North Carolina Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8078-9573-3. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Logan, Rayford W. (1969). Howard University: The First Hundred Years, 1867 - 1967. New York University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8147-0263-5. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Jackson, Cynthia L.; Nunn, Eleanor F.. (2003). Historically Black Colleges and Universities: a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-85109-422-6. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Smith, 2002, p. 134–135.

- ↑ Konhaus, Timothy (2006). «Delany, Martin Robison». Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass 2. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 373-375. ISBN 9780195167771.

- ↑ Finkelman, Paul (2007). «Not Only the Judges' Robes Were Black: African-American Lawyers as Social Engineers». En Steve Sheppard (ed.), ed. The History of Legal Education in the United States: commentaries and primary sources 1. Clark, N.J: The Lawbook Exchange. pp. 913-948. ISBN 9781584776901.

- ↑ Sharfstein, Daniel J. (22 de febrero de 2011). «Orindatus Simon Bolivar Wall». Slate.com. ISSN 1091-2339. Archivado desde el original el 6 de abril de 2015. Consultado el 30 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ a b Potter, Joan (2009). African American Firsts: Famous, Little-known, and Unsung Triumphs of Blacks in America. Kensingston Publishing Corporation. pp. 26-27. ISBN 978-0-7582-4166-5. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Holland, Jesse J. (2007). Black Men Built the Capitol: Discovering African-American History In and Around Washington,. Globe Pequot. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-7627-5192-1. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Lynch, Matthew (31 de octubre de 2012). Before Obama: A Reappraisal of Black Reconstruction Era Politicians. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1-2. ISBN 978-0-313-39792-9. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Stodghill, Ron (25 de mayo de 2008). «Driving Back Into History». The New York Times. p. 1.

- ↑ «John Willis Menard of Louisiana became the first African American to address the U.S. House». Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. 2 de noviembre de 2012. Archivado desde el original el 7 de abril de 2011.

- ↑ Bartley, Abel A. (16 de enero de 2003). «Bassett, Ebenezer Don Carlos». En James George Ryan and Leonard C. Schlup (eds.), ed. Historical dictionary of the Gilded Age. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765621061. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Linda Joyce Brown (16 de abril de 2006). «Coppin, Fanny Jackson». En Elizabeth Ann Beaulieu (ed.), ed. Writing African American Women. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 220-222. ISBN 0313024626. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Teasley, Mary D.; Walker-Moses,, Deloris, curators (2000). «African-American Firsts Remembered: Lest We Forget». The Newark Public Library. Archivado desde el original el 16 de mayo de 2014. Consultado el 5 de noviembre de 2008.

- ↑ Sollors, Werner; Titcomb, Caldwell; Underwood, Thomas A. (1993). Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-american Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe. New York: New York University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8147-7973-6. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Wasniewski, Matthew (27 de agosto de 2012). Black Americans in Congress, 1870-2007. Government Printing Office. pp. 54-61. ISBN 978-0-16-086948-8. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Hine, William C. «Rainey, Joseph Hayne (1832-1887)». En Walter B. Edgar (ed.), ed. South Carolina Encyclopedia. Columbia, South Carolina: Institute for Southern Studies, University of South Carolina. Archivado desde el original el 10 de noviembre de 2013. Consultado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Harley, Sharon (1996). The timetables of African-American history: a chronology of the most important people and events in African-American history. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684815787. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Dray, Philip (2008). Capitol men: the epic story of Reconstruction through the lives of the first Black congressmen. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-618-56370-8. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Deskins, Donald R.; Walton, Hanes; Puckett, Sherman C. (2010). Presidential Elections: 1789 - 2008 ; County, State, and National Mapping of Election Data. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-472-11697-3. Consultado el 27 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ «NTEU Celebrates Black History Month: Joseph H. Rainey (1832-1887)». National Treasury Employees Union. Archivado desde el original el 7 de marzo de 2013.

- ↑ Mickens, Ronald E. (2002). Edward Bouchet: The First African-American Doctorate. World Scientific Publishing Company Incorporated. ISBN 9789810249090.

- ↑ Flipper, Henry (1878). The Colored Cadet at West Point. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803268904.

- ↑ Nicas, Jack (27 de junio de 2010). «Boston’s first black officer receives his long-overdue honors». The Boston Globe. Archivado desde el original el 12 de enero de 2015. Consultado el 13 de noviembre de 2012.

- ↑ Hoffbeck, Steven R. (2005). Swinging For The Fences: Black Baseball In Minnesota. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-87351-517-7. Consultado el 4 de julio de 2013.

- ↑ Darraj, Susan Muaddi (1 de enero de 2009). Mary Eliza Mahoney. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438107609.

- ↑ O'Toole, James M. (2004). «Healy, Michael». En Henry Louis Gates; Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, eds. African American Lives. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 387-388. ISBN 978-0-19-988286-1. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Sewell, George Alexander; Dwight, Margaret L. (20 de enero de 2012). Mississippi Black History Makers. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 16-17. ISBN 978-1-61703-428-2. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Hine, Darlene Clark (2005). Black women in America 1. Oxford University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-19-515677-5. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Gendin, Sidney (1999). «Moses Fleetwood Walker: Jackie Robinson's accidental predecessor». En Joseph Dorinson, ed. Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream. Joram Warmund. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 22-29. ISBN 978-0-7656-3338-5. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ a b Sluby, Patricia Carter (2004). The Inventive Spirit of African Americans: patented ingenuity. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-275-96674-4. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ «A History of African Americans in the NYPD». The New York City Police Museum. Archivado desde el original el 22 de diciembre de 2008.

- ↑ Tardif, Elyssa (2013). Providence's Benefit Street. Arcadia Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7385-9923-6. Consultado el 31 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Kinshasa, Kwando M. (2006). African American Chronology: chronologies of the American mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-313-33797-0. Consultado el 31 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Moore, Jacqueline M. (2003). Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. DuBois, and the Struggle for Racial Uplift. The African American history series. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8420-2994-0. Consultado el 31 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Robert Henry Miller (1995). The Story of "Stagecoach" Mary Fields. Silver Burdett Press. ISBN 978-0-382-24399-8. Consultado el 31 de mayo de 2013.

- ↑ Aaseng, Nathan (1 de enero de 2003). «Taylor, Marshall Walker». African-American Athletes. Facts on File library of American history. New York, NY: Infobase Publishing. p. 218. ISBN 1438107781.

- ↑ Davis, Deborah (5 de febrero de 2013). Guest of Honor: Booker T. Washington, Theodore Roosevelt, and the White House Dinner That Shocked a Nation. Atria Books. ISBN 978-1-4391-6982-7. Consultado el 1 de junio de 2013.

- ↑ Grasso, John (15 de noviembre de 2010). «Lew, Harry Haskell "Bucky"». Historical Dictionary of Basketball. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810875063.

- ↑ Marlowe, Gertrude Woodruff (2003). A right worthy grand mission: Maggie Lena Walker and the quest for Black economic empowerment. Howard University Press. ISBN 978-0-88258-210-8. Consultado el 1 de junio de 2013.

- ↑ Conner, Floyd (31 de octubre de 2001). The Olympic's Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of the Olympics' Gold Medal Gaffes, Improbable Triumphs, and Other Oddities. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-59797-397-7. Consultado el 1 de junio de 2013.

- ↑ Manolis, Paul G (1981). «Raphael (Robert) Morgan, the First Black Orthodox Priest in America». Theologia Athinai 52 (3): 464-480.

- ↑ Smith, Charles R. (22 de junio de 2010). Black Jack: The Ballad of Jack Johnson. Roaring Brook Press. ISBN 978-1-59643-473-8. Consultado el 1 de junio de 2013.

- ↑ Potter, 2002, p. 345–346.

- ↑ Susan Love Brown (2006). «Economic Life». En Paul Finkelman (ed.), ed. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895: from the colonial period to the age of Frederick Douglass 1. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 121-129. ISBN 0195167775.

- ↑ a b Wilson, Joseph; David Addams (2006). «Football». En Paul Finkelman (ed.), ed. Encyclopedia of African American history, 1619–1895 1. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 234-237. ISBN 0195167775.

- ↑ Uzelac, Constance Porter; Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (23 de marzo de 2004). «Coleman, Bessie». En Henry Louis Gates (ed.), ed. African American Lives. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 182-184. ISBN 9780199882861.

- ↑ Malveaux, Julianne (1997). «Missed Opportunity: Sadie Teller Mossell Alexander and the Economics Profession». En Thomas D. Boston, ed. A Different Vision: Africa American Economic Thought 1. Routledge Chapman & Hall. pp. 123-. ISBN 978-0-415-12715-8. Consultado el 4 de junio de 2013.

- ↑ «William Dehart Hubbard First Black to Win Gold in an Individual Event». Jet 90 (10). 22 de julio de 1996. pp. 60-61. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ↑ «Clifton R. Wharton Sr. Dies; Foreign Service Pioneer, 90». Jet 78 (5). 14 de mayo de 1990. p. 16. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ↑ «The Clash of New York's Irish and Italians, and the City's First Black Firefighter». New York Times. 7 de agosto de 2015. Consultado el 17 de septiembre de 2015. «Wesley Williams, who was inspired by Battle, enlisting as a firefighter in 1919. ...»

|periódico=y|publicación=redundantes (ayuda) - ↑ Baker, Josephine; Bouillon, Joe (1977). Josephine (Primera edición). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-010212-8.

- ↑ Committee on House Administration; Office of History and Preservation (2008). «Oscar Stanton De Priest, 1871–1951». En Matthew Wasniewski (ed.), ed. Black Americans in Congress, 1870–2007. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 278-285. ISBN 9780160801945.

- ↑ Weber, Bruce (19 de julio de 2008). «Sherman L. Maxwell, 100, Sportscaster and Writer, Dies». The New York Times. Consultado el 13 de agosto de 2008.

- ↑ «The Path Foward: Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr.». The Washington Post (en inglés). 25 de enero de 2021.

- ↑ «Gen. Michael Langley Marine Corps first black four-star general». United States Marine Corps (en inglés). 6 de agosto de 2022.

Bibliografía

editar- Smith, Jessie Carney (2002). Black Firsts (2 edición). Detroit: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-258-6. Consultado el 29 de mayo de 2013.

- Potter, Joan (2002). African-American Firsts: famous, little-known and unsung triumphs of Blacks in America (Modif. y ampliada, ed edición). New York: Dafina Books. ISBN 0758202431. Consultado el 30 de mayo de 2013.

Enlaces externos

editar- President Obama's Speech to the NAACP on July 16, 2009 – full video by MSNBC

- Weiner, David * "African-American Firsts In New York", The Huffington Post, August 4, 2009

- Mance, Ajuan "Timeline: Black Firsts in Higher Education", Blackoncampus.com, November 5, 2009